Yesterday, I read a blog with some statistics I’ve seen quoted many times: only 30% of PhDs proceed in academia, no more than 12% manage to obtain a permanent position, and a mere 0.5% become a full professor.

Is doing a PhD really such a brutal process of selection where almost nobody survives the onslaught? After 25 years in academia, I thought this would be a good moment to compute my own statistics. And they are quite different.

By the way, the blog was an interesting story by Özlem Bulut, a PhD candidate at the medical center where I work about the big research reorganization my institution is currently executing. Maybe I’ll write about that in another article.

Who says only 1 in 200 PhDs become professors?

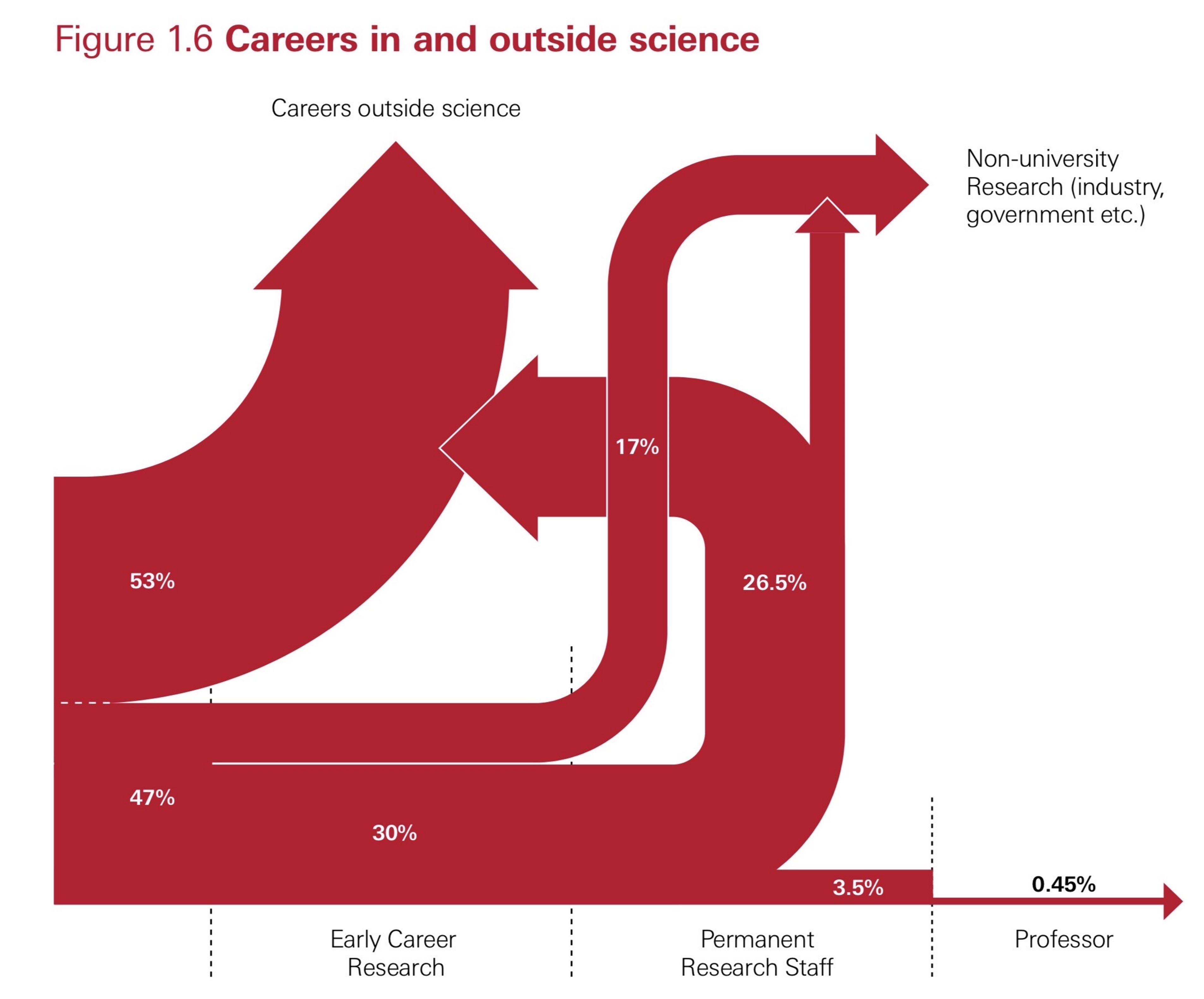

These statistics come from a figure in a 2010 report from the Royal Society, shown below.

According to this plot, it is even harder to get a permanent position in the university than what Özlem wrote, not 12% but 3.5%.

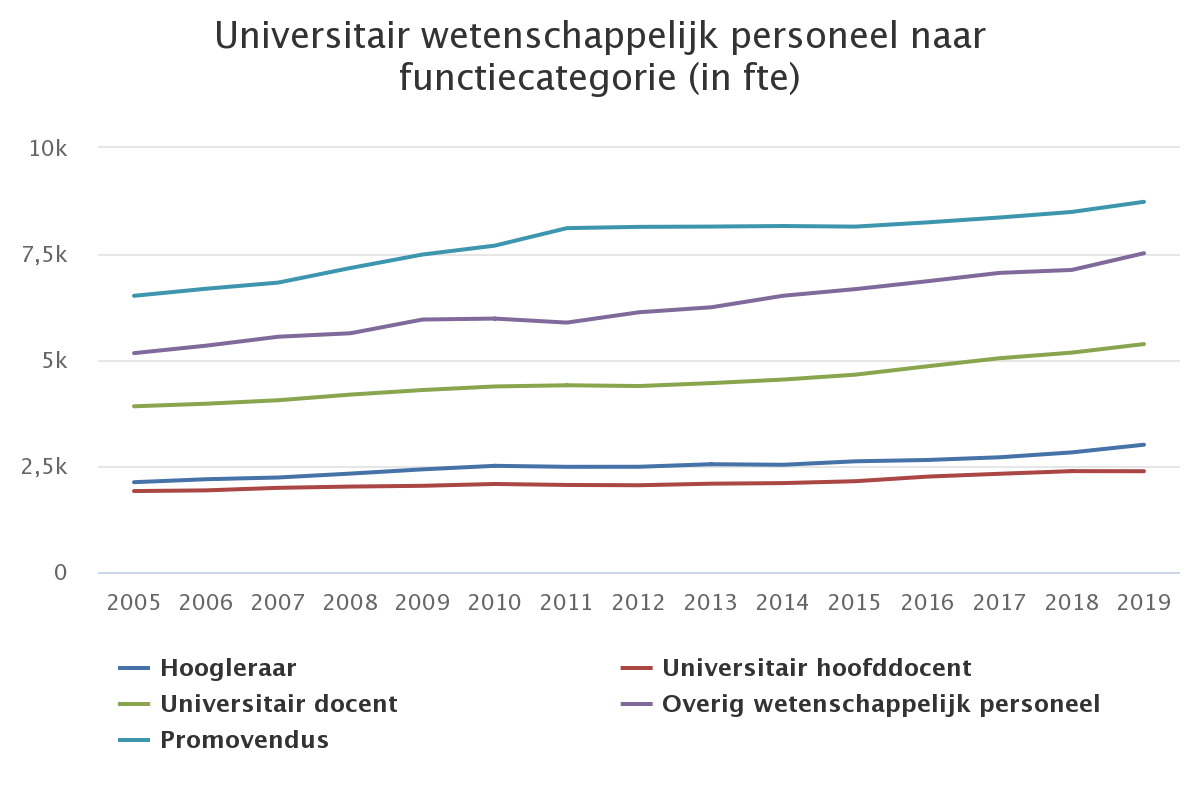

But do these old UK numbers apply to the current situation in The Netherlands? The Rathenau Institute regularly publishes insightful reports about research, science, innovation and technology in The Netherlands. In a recent factsheet they gave these figures from 2019 on the number of researchers working at Dutch universities:

- 8.731 fte PhD students (32%)

- 7.518 fte other research personnel (teaching positions and postdocs, 28%)

- 5.376 fte assistant professors (20%)

- 2.377 fte associate professors (9%)

- 3.002 fte full professors (11%)

This number of 3002 full professors is up from 2118 in 2005, an increase of 42%. The number of PhD students grew by only 34%. So it may have even become a bit easier to get that beautiful gown. Here is a graph:

The Rathenau factsheet adds that PhD students are on average 29 years old when they defend their thesis. Researchers appointed to assistant professor are on average 37, associate professors start at 42 and full professors are appointed at the age of 49. From PhD defense to full professors it takes on average a whopping 19 years!

I think these numbers already indicate that the estimate that only 0.45% of PhDs make it to full professor is way too low. There are around 3 PhD students per full professor. Completing a PhD in the Netherlands takes 4 years (usually longer in practice, that’s annoying and worth another story, but you get paid for four years, at least in my field). If we assume all professors work for 20 years before they retire (they are already nearly 50 years old when they start so this is a generous estimate), then each professor brings around 15 PhDs to the finish line as one of their promotors (supposing, incorrectly, that all PhD students graduate). If we assume one of these students will succeed her or him (maybe the successor comes from abroad, but then, Dutch PhDs can become professors abroad as well), we should have 1 in 15 becoming a professor and not 1 in 200.

What about my group?

I worked as a supervisor of PhD students and postdocs at two Dutch UMCs, in Utrecht from 2001 to 2010 and in Nijmegen from 2010 until today. My field is medical image analysis. Researchers in my group develop systems (they build software using machine learning) to analyze scans and detect abnormalities, outline and quantify structures, etc. We used to call this computer-aided diagnosis, now we call it AI. More and more often, these AI systems are now performing well enough to be actually useful in clinical practice. But does the success of my field of research (or, as some say, the hype of biblical proportions around AI), also translate into academic success for the students I worked with?

I took my list of publications and looked at the first authors of all these works. I extracted all PhD students or postdocs that worked in my group. I left out PhD students who quit (more on that below) and students still working on their PhD. This gave me a list of 60 names. I was not always the primary supervisor, co-promotor or promotor of these researchers, but at least I co-authored one of their papers.

To go directly to the primary metric of interest for this blog: four of my former co-workers have become full professor. This is exactly the estimate of 1 in 15 that I made above!

These four all became professors in less than the average of 19 years after their PhD. The first one became a professor in Copenhagen only 9 years after graduating. Faster than it took me (11 years). The second one was appointed in Amsterdam 12 years after her PhD. The third one was not somebody I supervised; we both worked as PhD students at the same time and did some joint research. She became professor in Rotterdam 17 years after graduating. The fourth one came as a postdoc to my lab, went with me from Utrecht to Nijmegen, was promoted there to associate professor and is now full professor in Amsterdam 12 years after graduating.

We should account for the fact that most researchers on my list of 60 graduated only recently and it is, therefore, to be expected that none of them are already professors. Only 15 researchers on the list were postdocs working with me or graduated in my group in 2010 or earlier; this group includes the four professors. If I look at the full list, I’m confident there will be several more who will be professors someday; 11 are still working in academia. Four have permanent positions.

Luckily, not everybody wants to be a professor. So what do most people do after working in my group? Most of them (21 people, 35%) currently work in industry, doing something directly related to their PhD or postdoc research, in almost all cases medical. Seven of them work abroad (two in the United States and in Germany, one in the UK, in Korea, and in Australia). Seven work for Thirona, the company that a former PhD student of mine started and she is still leading. And talking about startups, another former PhD student started a company, two are about to start one, and one is joining a startup still in stealth mode as one of the first employees. Only 10% are working in a job not related to image analysis or machine learning, mostly in IT or computer science.

I’ve (co-)supervised several medical doctors. There are nine former PhD students now working as a radiologist or a radiology resident; none of them deviated from the course they set out to follow. Several still find the time to do research as well. The staggering workload for radiologists in the Netherlands makes it difficult to pursue such a dual career.

Finally, there are five students who started a PhD and did write one or more papers but decided not to continue the PhD at some point. I did not include them in my list of 60. This is a pretty high percentage of dropouts, and there are also several students that have quit before a first paper was published. Sometimes there were personal reasons for not continuing, but this shows that doing a PhD is not for everybody, and it is a sign that I still find it very difficult, even though I’ve been through many hiring processes, to predict who will be successful as a graduate student.

In conclusion, stating that it is almost impossible to get a permanent position at the university after doing a PhD and that only 1 out of 200 PhD graduates becomes a professor is a myth. For those of you who want to have an academic career, the odds are maybe not outstanding, but certainly a lot better than 1:200 and you really do not always have to work for two decades before you give that inaugural lecture. If you do research around applications of AI in healthcare, there are a lot of opportunities to get a job in industry related to your field, or even start your own company.